LGS Blog

LGS announces its Summer Academy 2015

The London Graduate School

Summer Academy in the Critical Humanities

June 22-25 2015

Right to Philosophy

Featuring Etienne Balibar, Andrew Benjamin, Howard Caygill, Rebecca Comay, Catherine Malabou, Martin McQuillan, Simon Morgan Wortham, Stella Sandford and Bernard Stiegler

The London Graduate School is pleased to announce its 2015 Summer Academy, an intensive week-long programme offered annually for postgraduate students of any institutional affiliation. This year the theme of the Summer Academy is Derrida’s Right to Philosophy. Once more the event will be held in central London, and the venue is University College London.

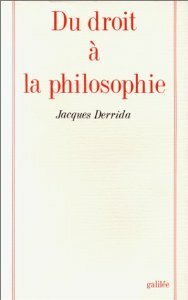

The ensemble of texts found in Du droit à la philosophie reflect Derrida’s engagement from the 1970s onwards with French political debates about the reform of national education and the future of philosophy teaching in the university in France and beyond. Here, he intervenes in the question of the institutional conditions and possibilities of philosophy as both an historical legacy and ongoing provocation to the future.In 1975 Derrida co-founded the Greph (Group de Recherches sur L’Enseignment Philosophique), a group committed both to theoretical investigation and activist intervention. Greph was founded in response to a perceived political and ideological attack on philosophical education on the part of the French government, operating under the general sponsorship of a matrix of economic, political, and techno-industrial and techno-military powers. While the election of Mitterand’s socialist government in 1981 hardly brought such concerns to a satisfactory conclusion, a state initiative was launched to establish an international college of philosophy in France, and Derrida took a leading role in the difficult process of negotiation and consultation that led to its inauguration in 1983, becoming the first director. At the time this call was being finalised, we learned of the threat of closure of the Collège international de philosophie (CIPH), which must surely provoke a renewal of the struggles that characterised its founding.

For Derrida, philosophy’s asymmetrical contract with the university—neither belonging nor not-belonging to the institution as a part of the whole, the universitas, which it itself allots—makes possible an opening on to the very question of the structure and effects of the university space, not least in its relations with the wider world (although Derrida is always most vigilant about the very fragile and deconstructible relationship between the supposed ‘inside’ and ‘outside’ of the institution). In other words, it is philosophy’s ‘with-against’ relation to the university that often interests Derrida in his interventions in political debates about French educational reform during this period. Derrida is less concerned with a straightforward defence of philosophy in its accepted scholarly guise than in transformative moves and gestures that make possible the ‘other’ of philosophy itself. Here, the question of the right to philosophy acquires a multiple sense. Whether one can ever proceed to the ‘philosophical’ directly as much as whether philosophy is a duty, privilege or justification (itself a question that is not always well served by excessive ‘directness’) is posed by Derrida as, among other things, a continued provocation to the question of the institution. If such questions about philosophy, the university and its ‘outside’ are just as urgent and pressing now as they were forty years ago, it is to the extent that they also make possible a certain powerful and productive resistance to discourses about what is ‘urgent’, dutifully or directly necessary, unanswerably pragmatic, and so forth—discourses that strongly facilitate dominant forms of governmentality and power today. The plight of the CIPH–still uncertain despite its apparent reprieve–is of course linked to a political discourse of pragmatism, so it is in this vein that our focus will very much be on the continuing relevance of Right to Philosophy as much as its historic context.

Programme

Monday 22nd June

1pm Registration and Welcome

Simon Morgan Wortham and Martin McQuillan (Kingston University)

South Wing 9 Garwood Lecture Theatre

2-4pm Bernard Stiegler (IRI)

“Facts and rights. Making the différance between code and law”

South Wing 9 Garwood Lecture Theatre

Tuesday 23rd June

10.30-noon Andrew Benjamin (Monash University and Kingston University)

“‘Je n’en sais rien’: Knowing after ‘nothing’. Proceeding after Deconstruction”

South Wing 9 Garwood Lecture Theatre

12-1.30pm Reading Groups, led by Chiara Alfano (Kingston University) and Daniel Hoffman-Schwartz (Princeton University)

Foster Court 130 and Foster Court 132

2.30-4pm Stella Sandford (Kingston University)

“Privilege”

Pearson North East Entrance G22 Lecture Theatre

Wednesday 24th June

10-11.30am Reading Groups, Chiara Alfano and Daniel Hoffman-Schwartz

Foster Court 130 and Foster Court 132

11.30-1.30pm Rebecca Comay (University of Toronto)

“Leverage”

Pearson North East Entrance G22 Lecture Theatre

2.30-4pm Howard Caygill (Kingston University)

“That Perhaps Abused Word…”

South Wing 9 Garwood Lecture Theatre

Thursday 25th June

10.30am-noon Reading Groups, Chiara Alfano and Daniel Hoffman-Schwartz

South Wing G12 Council Room and South Wing 9 Garwood Lecture Theatre

1-2.30 Catherine Malabou (Kingston University)

“Philosophical Commons and the French Republic”

Pearson North East Entrance G22 Lecture Theatre

3-4.30 Etienne Balibar (Columbia University and Kingston University)

“Which conditions for a ‘University without Conditions’? Rereading Derrida’s profession of faith fifteen years later”

Pearson North East Entrance G22 Lecture Theatre

Key Reading:

‘Privilege: Justificatory Title and Introductory Remarks’ in Who’s Afraid of Philosophy: Right to Philosophy I (Stanford University Press, 2002)

‘Mochlos’, ‘Vacant Chair’, and ‘The Principle of Reason’ and in Right to Philosophy 2: Eyes of the University (Stanford University Press, 2004)

Immanuel Kant, ‘What Does it Mean to Orient Oneself in Thinking?’ in Allen W. Wood and George Di Giovanni, eds (Cambridge University Press, 1996)

First of Kant’s Conflict of the Faculties